August 7, 2014 – The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) oversees a disability program that makes payments through the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) to compensate U.S. veterans for medical conditions or injuries that are incurred or aggravated during active duty in the military, although not necessarily during the performance of military duties. Compensable service-connected disabilities range widely in severity and type, including the loss of one or more limbs, migraines, scars, and hypertension. Payments are meant to offset the average earnings lost as a result of those conditions, whether or not a particular veteran’s condition has reduced his or her earnings or interfered with his or her daily functioning. Disability compensation is not means-tested; veterans who work are eligible for benefits, and, in fact, most working-age veterans who receive disability benefits are employed. Payments are in the form of monthly annuities and typically continue until death.

Adjusted for inflation to 2014 dollars, VA disability compensation to veterans amounted to $54 billion in 2013, or about 70 percent of VBA’s total mandatory spending, according to analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The remainder of the department’s mandatory spending that year was for programs that provide veterans with housing assistance, education, vocational training, and other assistance. In 2013, about 3.5 million of the nation’s 22 million veterans received disability compensation benefits. (Those benefits are distinct from the health benefits provided through the Veterans Health Administration [VHA].)

How Much Has Federal Spending on VA Disability Changed Since 2000?

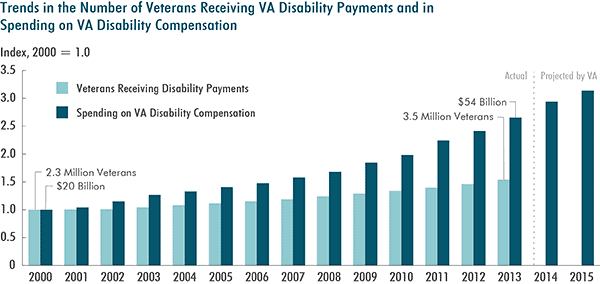

From 2000 to 2013, the number of veterans who were receiving disability payments rose by almost 55 percent, from 2.3 million to 3.5 million (see Figure 1 below), despite a 17 percent decline in the total population of living veterans, from nearly 27 million to 22 million. In 2000, 9 percent of all veterans received disability benefits; by 2013, that proportion had risen to 16 percent. Over the same period, the average real (inflation-adjusted) annualized disability payment also rose by nearly 60 percentfrom $8,100 in 2000 to $12,900 in 2013consistent with increases in the average number and average severity of compensable disabilities per veteran.

Both the share of veterans receiving disability payments and the average real amount of those payments increased for veterans from all periods of service. Those increases can be attributed to several factors: changes in policy that made it easier for veterans to claim benefits, the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and difficult labor market conditions during the past several years.

Spending on veterans’ disability benefits has almost tripled since fiscal year 2000, from $20 billion in 2000 to $54 billion in 2013. VA projects that obligations will total $60 billion in 2014 and $64 billion in 2015, a 19 percent increase from two years earlier (see Figure 1).

How Might Certain Policy Options Affect the Federal Budget?

The United States has a record that spans centuries of compensating veterans who have been injured during military service. VBA’s vision statement reads, in part, “Veterans whom we serve will feel that our Nation has kept its commitment to them… and taxpayers will feel that we’ve met the responsibilities they’ve entrusted to us.” To better meet those purposes, lawmakers could consider changing VA’s disability compensation program. In response to budgetary pressures, for example, the program could be scaled back to reduce federal spending. Alternatively, lawmakers could choose to modify the program to provide greater support to certain groups of disabled veterans.

In this report, CBO examines some advantages and disadvantages of potential policy changes and presents estimates, to the extent that it is possible to do so, of their budgetary effects from 2015 through 2024 (see Table 1). Several of the options would modify VA’s processes for identifying service-connected disabilities. Others would change payment rates, coordination with other federal benefits, or the tax treatment of benefits.

| Budgetary Effects of Selected Approaches to Changing Veterans’ Disability Compensation | ||

| Billions of Dollars | Ten-Year Savings (Costs), 20152024 | |

| Modify VA’s Processes for Identifying Service-Connected Disabilities | ||

| Option 1: Institute a Time Limit on Initial Application | ||

| 5 years | 28 | |

| 10 years | 19 | |

| 20 years | 9 | |

| Option 2: Require VA to Expand Its Use of Reexaminations | Could be savings or costsa | |

| Option 3: Change the Positive-Association Standard for Declaring Presumptive Conditions | Net savingsa | |

| Change Payments to Disabled Veterans | ||

| Option 4: Restrict Individual Unemployability Benefits to Veterans Who Are Younger Than the Full Retirement Age for Social Security | ||

| All veterans | 17 | |

| Phased in for veterans age 65 or younger in 2015 | 8 | |

| Option 5: Supplement Payments to Veterans Who Have Mental Disorders | ||

| All veterans | (9)b | |

| Veterans age 65 or younger | (7)b | |

| Option 6: Change the Cost-of-Living Adjustment | 10 | |

| Option 7: Change Concurrent Receipt | ||

| Eliminate the program | 119 | |

| Extend to all DoD retirees | (30) | |

| Option 8: Tax VA Disability Payments | 64 | |

| Sources: Congressional Budget Office; staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation. Note: VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; DoD = Department of Defense. a. CBO did not estimate the budgetary effects of this option. b. The cost represents two years of supplemental payments. | ||

The option with the largest estimated budgetary effect would eliminate the program known as concurrent receipt. For decades before 2003, a veteran’s retirement pay from the Department of Defense (DoD) was reduced by the amount of any VA disability benefits that person received. Since then, under concurrent receipt, the retirement pay some veterans receive either is not reduced or is reduced by a smaller amount. CBO estimates that eliminating concurrent receipt (and thereby returning to the previous longstanding policy) would save the federal government $119 billion from 2015 through 2024. By contrast, extending concurrent receipt to all veterans who would be eligible both for disability benefits and for military retirement pay would cost $30 billion over the same period. The estimated budgetary effects of the other options range from savings of $64 billion through 2024 to additional outlays of $9 billion for the same period. (Actual savings or costs would depend on the options’ final design.)